Late one afternoon not long ago, a fellow got me on the phone for tech support. He said he had ten carbon dioxide transmitters on one DCP-1.5-W power supply, and they weren’t operating, and he had pulled out most of his hair. Each transmitter needs less than 100 mA to operate, so the 1.5A power supply should have been more than enough.

He had applied power to the transmitters one by one, and all was well until he connected the fifth unit. At that point, the voltage dropped from 24 volts to 6, and it continued to drop bit by bit as he connected additional units. He checked everything, he said—he even powered up each individual unit directly from the power supply—and they were all just fine. What to do?

After receiving his wiring diagram by e-mail, I called him back and asked him to hook up all ten units as shown on his diagram so that he could test each point while on the phone with me. With his voltmeter negative lead alligator-clipped to the power supply negative, he started measuring voltages. At the power supply positive, he called out “24.” At his 115SP terminal strip, he called out “24” again. Going down the strip, he called out “24” four more times, at each of the first four connected units. At the fifth terminal, he called out “6,” and added, “See what I’m talking about?”

Now, this fellow is an old hand—I didn’t have any reason to doubt his ability to strip a wire and hook it to a terminal—but there was no denying the voltage was going away at that one point. So after a minute’s thought, I said to him, “The terminal showing 6 volts has two screws, right? Humor me and check them both.” After a short debate, he agreed, and he found that the missing 18 volts was being dropped across what appeared to be a perfectly good wiring terminal! He replaced the terminal strip next, and his system was ready for commissioning.

The next afternoon, he called me back to say that he was so curious about that terminal that had caused him such grief that he got his die grinder out and removed the terminal’s plastic insulation. That’s when he discovered that the internal bus was cracked all the way across— it was just luck that it was making enough contact to show 6 volts on its downstream side.

Strange but true! The lesson I learned was this: before we claim to have checked everything, it’s a good idea to broaden our definition of “everything.” Wires can be broken in the middle, terminals can be cracked—it only takes a second to check, and it might make the difference between a good night’s sleep and a frustrating all-nighter.

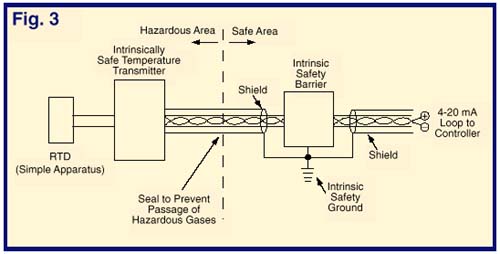

So, if we have an RTD and an intrinsically safe temperature transmitter in a hazardous location, can we wire them up to our controller and power supply in the safe area and turn them on? Not yet! Three more steps are needed first. While the devices in the hazardous area cannot ignite the gas mixture on their own, the controller and power supply in the safe area may each be capable of transmitting enough energy through the wires into the hazardous area to do the job anyway! An

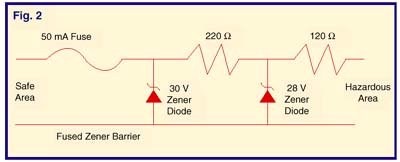

So, if we have an RTD and an intrinsically safe temperature transmitter in a hazardous location, can we wire them up to our controller and power supply in the safe area and turn them on? Not yet! Three more steps are needed first. While the devices in the hazardous area cannot ignite the gas mixture on their own, the controller and power supply in the safe area may each be capable of transmitting enough energy through the wires into the hazardous area to do the job anyway! An  Figure 2 illustrates a simple zener diode barrier circuit. A high voltage at the safe side terminals will cause the zener diode to draw a high current and blow the input fuse. The series resistors limit the current to the hazardous side. Barriers are also rated for how much capacitance and inductance are allowed on the hazardous side.

Figure 2 illustrates a simple zener diode barrier circuit. A high voltage at the safe side terminals will cause the zener diode to draw a high current and blow the input fuse. The series resistors limit the current to the hazardous side. Barriers are also rated for how much capacitance and inductance are allowed on the hazardous side. The final factor to consider is grounding. What good is all this built-in electronic safety if a nearby lightning strike raises the ground potential a couple of thousand volts above the potential of the cable shield in our hazardous area? The resulting arc from the shield to ground can be every bit as effective as a butane lighter in touching off an explosion, and we needn’t have bothered with using intrinsically safe products. An intrinsic safety ground, bonded to the earth ground, is the last essential link that makes the system work. Normally provided at the barrier location, it keeps the cable shields at or near the same potential as the earth, even as that value moves around during storms.

The final factor to consider is grounding. What good is all this built-in electronic safety if a nearby lightning strike raises the ground potential a couple of thousand volts above the potential of the cable shield in our hazardous area? The resulting arc from the shield to ground can be every bit as effective as a butane lighter in touching off an explosion, and we needn’t have bothered with using intrinsically safe products. An intrinsic safety ground, bonded to the earth ground, is the last essential link that makes the system work. Normally provided at the barrier location, it keeps the cable shields at or near the same potential as the earth, even as that value moves around during storms.