Let’s start with a riddle:

Q: They’re dirty, they’re annoying, they cause all sorts of trouble, they make everyone uncomfortable, and they’re hard as heck to catch; but, they’re not the pesky flies that buzz around one’s picnic potato salad? What are they?

A: Humidity sensors abused by hostile environments.

You’d be surprised where we find hostile environments. They’re not always in industrial plants and oil fields. At one point, the office in which I sit was a hostile location. On occasion, it still is. Read on.

Condensation

Believe it or not, humidity can be hostile to a humidity sensor. That is, humidity is hostile when the moisture in the air is allowed to condense into liquid water on the surface of the sensor or its electronics.

Any time an object’s surface temperature is below the dew point of the surrounding air, condensation will form on the object. If the object is exactly at the dew point or just a degree or so below it, a fine mist will form all over it. If the object is much colder, say 10°F (5.6°C) or more below the air’s dew point, a fully wet surface and active dripping will be the case. To prove the latter case to yourself, take a frosty cold can of your favorite soda outside on a muggy summer day and observe the puddle wherever you set it down.

So how is this hostile to a humidity sensor? After all, being wet is just the same as 100 percent relative humidity, right? Wrong. When we say 100 percent relative humidity, we mean that the air is holding all of the water vapor it can hold at a given dry-bulb temperature. We use the term saturated air for this condition, and it is a special point at which the air’s dry bulb temperature is equal to its dew point temperature. Humidity sensors handle that just fine. Saturated air does not necessarily mean that the surfaces of things are wet. In fact, is unlikely that a humidity sensor or its electronic parts are wet because they each dissipate a little bit of power; this power warms them, so their temperatures should be a little bit higher than the surrounding air; their surfaces should be above the dew point temperature, so they should stay dry.

When a sensor gets wet, it will typically give a 100 percent humidity output. But it takes a while for it to dry out even after the surface condensation evaporates. Think of a humidity sensor as a tiny sponge. The liquid water that it has soaked up will take time to wick to the surface and evaporate even if drying conditions are good. If drying conditions are poor (high humidity), the time can be very long. Some sensors dry more quickly than others, but they all take time.

When the sensor finally gets dry, it has a new component to it. While water condensed from the air is pretty clean, it’s not perfectly pure. It leaves some residue on the surface from which it evaporated. One bit, or even a dozen, may not affect the accuracy of the sensor. Regularly repeated exposure to liquid will make those tiny bits of residue add up to a coating around the sensor that can seriously shift its calibration.

So what makes them wet, then?

Unusual conditions can cause a humidity sensor and its electronics to be colder than the dew point of the surrounding air, and there are also conditions in which other objects above the sensor get cold and drip condensation down on it. Here is an example, along with the solution that was employed to get proper humidity sensing back on track.

The Sensor is Blowin’ in the Wind…

The most prevalent occurrence of condensation indoors is when the humidity sensor lies within a room’s supply air stream during summer months in humid climates. One example came from a specialty retail store that required pretty good humidity control in its showroom. The store is located in a city with consistently humid outdoor air. Sorry, the names of the store and city are omitted to protect the innocent.

This store had supply air diffusers designed to discharge air across the ceiling at enough velocity that it did not fall until it reached the wall. Thus, anything mounted on the wall at the falling point can be considered to be sort-of in the supply air stream. That’s where this store’s humidity sensor was mounted. Unfortunately, it was also mounted fairly close to the store’s front door. On warm, humid days, the outdoor air would swoosh in when a customer opened the door. Also unfortunate was that the humidity sensor was directly in the path of that swoosh of warm, humid air. So, the sensor would be nice and chilly and then get hit with a blast of air with a dew point much higher than the sensor. This collision of warm humid air with the chilled sensor created instant wetness. Worse, it went on all day long, every day.

Not only did this poor sensor read 100 percent most of the time in the summer, it also was toast after only six weeks in place. When it was opened, it was obvious what had happened. The sensor element and all of the electronics were covered in a fine layer of dust. The contractor relocated the sensor toward the middle of the store, out of the way of any supply air and out of the way of the incoming air from the front door. The sensor then gave proper, accurate readings instead of bouncing up to 100 percent all day. It also lived happily ever after. It’s two years old at the time of this writing.

Corrosives and Other Nasties

The bulk of this article is about condensation because it seems to be the least understood of the humidity sensor enemies. Corrosives and other foreign substances (volatile organic compounds or VOCs) are more obvious destroyers, but some of them have sources that are not so obvious.

Silicones are the most surprising hostile substances for humidity sensors in general. Many instances have been reported in which silicone sealant has been used to caulk around an installed outdoor air humidity sensor’s wiring box or conduit body. A few indoor sensors to our knowledge have been attacked by the use of silicone sealant behind the sensor to insulate it from the wall cavity. One trouble with silicone sealants is that they emit the volatile part of the goop as it cures. The volatile part is typically a hydrocarbon solvent – not good for the innards of a sensor element. These vapors can shift the sensor’s calibration a bit. Repeated exposure can shift the calibration a lot. Another trouble is that uncured silicone sealant itself can spread rapidly over surfaces both by wicking and through air. This substance can shift the calibration of a humidity sensor by 2 percent to as much as 10 percent. If a sensor must be installed with the use of silicone sealant, wait until the silicone cures before installing the sensor. Even better would be to use an alternative like latex caulk.

Corrosives are harder to deal with. Some commonly encountered sources of corrosives include swimming pools, paints, paint strippers, solvents, wood preservatives, aerosol sprays, cleansers and disinfectants, moth repellents, air fresheners, stored fuels, automotive products, hobby supplies, dry-cleaned clothing, and personal care products. All of these things emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that are not friendly to humidity sensors and their electronics. As the term corrosives implies, these particular VOCs eat away at the sensing element and uncoated parts of their electronics.

When corrosives attack on a regular basis, the sensor will usually shift calibration slowly until it suddenly dies completely. A corrosion-resistant sensor can weather the attack and prolong the time between replacements. Some (very expensive) sensors are nearly immune to such corrosion and are typically found in industrial or laboratory environments.

Other Stuff can treat humidity sensors badly. For instance, plain old dust is very common. The effect of a routinely dusty environment will be a delayed response time that worsens as the dust gradually coats the sensing element. After totally enclosing the element or filling the elements filter, the output of the sensor’s response time will be so long as to present a steady output to the reading device or controller. One solution for dust is to place the sensor in an aspirated box with a washable or changeable filter.

Notes on Filtering: Some humidity sensors include a gas-permeable filter such as Gore-Tex® that does not allow passage of liquids or solids. That can be a big help in keeping the bad things away from the sensing element. It won’t stop condensation that occurs inside it from humid air, and it won’t stop corrosive gases. It will keep the sensor safe from dust, drips, and rain. The filter might require occasional cleaning, though. Sintered metal filters do a good job with particulate matter and an OK (but not perfect) job with dripping water or rain. They, too, may require occasional cleaning in dusty environments.

So how did my office become hostile to a humidity sensor? Let’s just say it involved a hot plate, some Indian food (chicken tikka masala), an office neighbor with a sensitive nose, and two cans of Lysol spray. I’ll leave the rest up to your imagination. My humidity sensor was a gone…

Conclusion

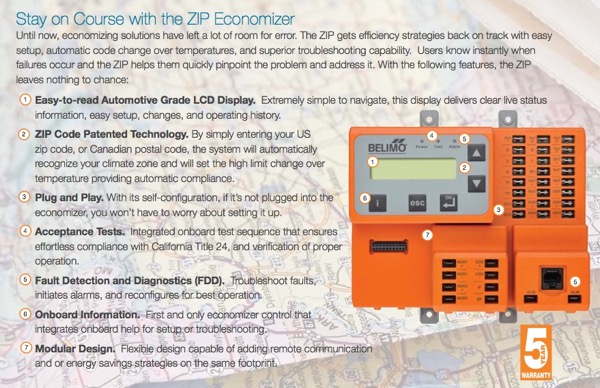

Ways can almost always be found to mitigate the effects of condensation, corrosives, and other nasties in the air that attack humidity sensors. The tough part is knowing what they are in advance. The easy part is calling Kele Technical Support at 877-826-9045 for assistance in winning your sensor’s battle against these elements.